Franz G Iseke

Lost Property is currently researching F Iseke: (d. 11/07/2010)

If ‘the Group’ were known as the ‘timber boys’ then Iseke was surely ‘the Steel man’! Franz, prior to arriving in New Zealand had been a submariner in the German Navy and was a keen advocate of space saving and waste removal.

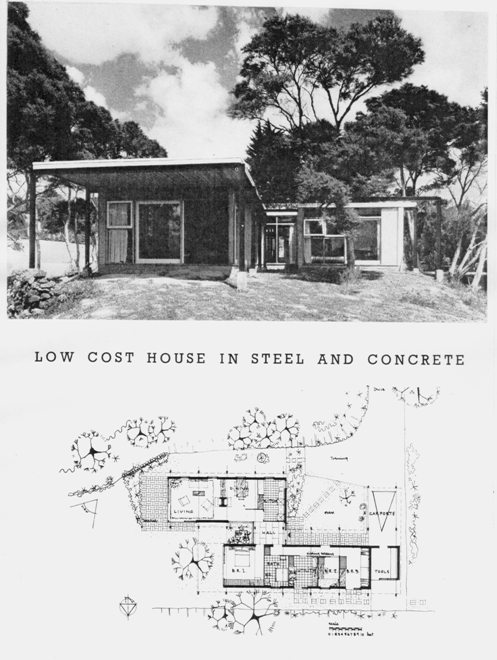

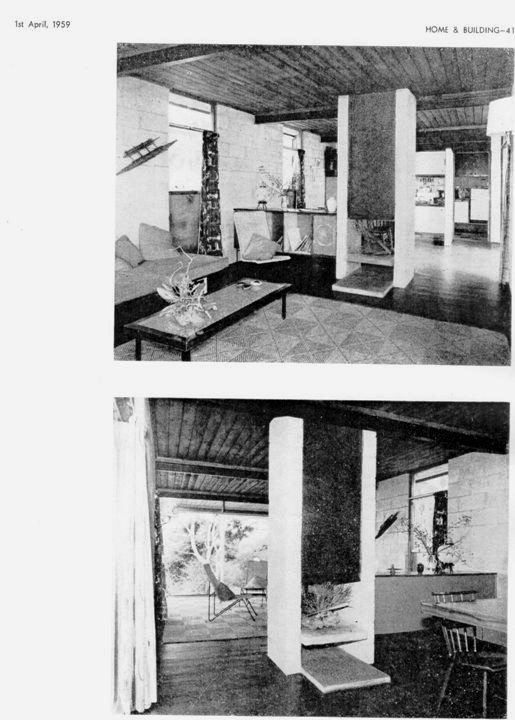

His own house built in Sprott Ave, Kohimarama (1958) is recorded as the first in Auckland to have fair-faced concrete block walls (and a roof supported on steel posts).. For this he was to engage in many battles with the Auckland City Council on the relative merits of non-load bearing concrete walls and steel post construction, who seemed reticent to believe the technical data which supported Franz’s work. The concrete slab base had steel re-inforced edge beams and was laid on a small plateau between two gullies with seaviews to Rangitoto. As such the house was basically divided into two blocks with the entrance vestibule acting as pivot to the two wings, one containing the sleeping area and the other the living room and kitchen, etc. The slightly angled roof was constructed of 6″ x 2″ tongue and groove pine, stained mahogany on the ceiling side, and covered in fibreglass and bitumen on the exterior. This was supported on 4″ steel posts at the eaves edge. Iseke points out the house was designed with cost saving in mind, not the waste of materials – traditional wooden houses containing “a forest of trees” in comparison. Costs for the completed house including floor coverings and curtains came to two pound, eighteen shillings per square foot ($5.80 sq ft) in 1958. Interior walls were covered in plywood or gibboard depending on area of use, and the concrete walls were left unpainted, which would appear in Ivan Juriss’s ‘Mann house’ two years later.

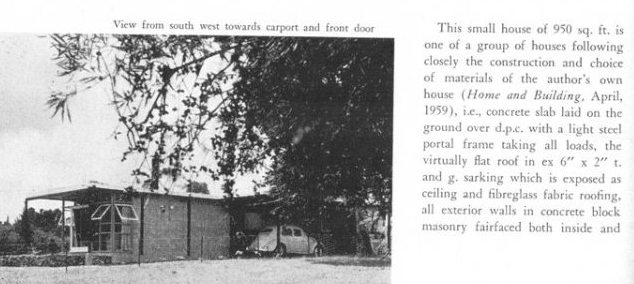

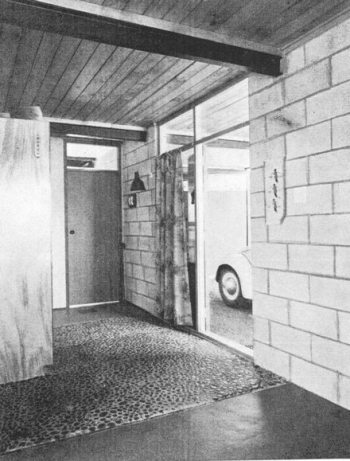

Franz built another house of a similar style (profiled in ‘Home & Building’ June 1960) for a retired couple: the article notes it is part of a number of houses he was working on which shared the same principles. In the Herald Island house, an ‘L’ shape of 950 sq.ft many of the earlier ideas resurface but are augmented by the owners input, such as the pebbled entrance area, using water-worn pebbles from the Thames coast. Concrete block walls are again left unpainted and contrast with the wooden panelling and metal accents. Colourful lino’s and cupboard doors enliven the work areas.

Born in Shanghai, in 1926 where his father had started a business flying post and freight to various parts of the province. The airline was later sold to the Chinese Government and moved to Chunking province were Franz’s father continued to manage the business which flew in the mountainous western region. Here Franz would live a wild and carefree childhood roaming the area until 1939 when visiting relations in Germany the family were trapped in the escalating conflict of what would become World War II.

Franz and family were then situated in Sudentland, which was previously Czhecholovakia; here his father was employed in the management of a factory making aircraft fusillades while the 13 year old Franz attended school. Shortly after his 16th birthday Franz was in the navy and training as a submariner.

His navel career was marred by time in prison for disobeying orders and being one of the few survivors of a U-boat blown out of the water in the North Sea. At wars end Franz then barely 19 years old returned to Bremen to study, doing a 6 month course to gain matriculation allowing entry to university. He also worked as a cabinetmakers assistant, qualifying in the trade after a year condensed course. Athough he had wanted to study at Stuttgart he did his final diploma in 1950 at the Munich University which would count influential tutors such as Sep Ruf on it’s staff. Franz earlier had been awarded a scholarship to study with Walter Gropius at Harvard and left for the States upon completion of his diploma year.

It seems Franz spent very little time studying in the States, initially working as part of a documentary film crew and then emigrating to Australia, arriving New Years Eve. Tall, blonde and able to speak several languages, he initially found work on the Sydney trams, later working as a translator. It was during this time that he would meet and marry Patricia, a gifted seamtress from near Whangarei staying in a Sydney hostel while working in the clothing industry. Shortly after the wedding Pat returned to Auckland and New Zealand with her new husband.

They arrived at a time when the country was still in the grip of wartime restrictions, with materials use and importation under the auspices of the ‘the Building Controller’, a governmental position which oversaw the construction industry. Improvements had been made in 1948, and as the 1950’s progressed restrictions were eventually removed allowing the country to enter a period of almost unparalleled growth and employment..

Joining the progressive practice of Cutter Thorp Pickmere & Douglas, Franz would meet many of the city’s present and future architectural designers like Mick Cutter, and Ralph Pickmere as well as working in the same office as Harold Marshall and Sandy Mill.

A man of considerable talent with a passion for life and fun, Franz was intent upon developing his own practice and within a few years was working from the newly completed home at 42 Sprott Rd in Kohimarama. These suburbs on the fringe of old monied Remuera were to be home to a number of unique architectural statements including Brenner Associates heroic ‘Paul home’ with its Butterfly roof. Franz’s house for his family would also stand out, somewhat amusingly used as direction in the Architecture Centre’s ill fated collection which described a Rigby Mullan design as “next to Iseke house”..!? (Sadly, the truly delightful Iseke house was destroyed by developers, and the Rigby Mullan house has had major cosmetic renovation..) Other houses by Iseke had been designed in the adjoining streets of the developing suburbs, though these don’t share quite the pared down rationalism of his own, and the other project for the retired couple on Herald Island. The Dover Place houses are considerably larger and closer in form to works by his tutors and influences at Munich, and also have similarities to the Dessau ‘Meisterhauser’s of Gropius. Franz’s design rational would remain heavily Bauhaus, and like other foreign architects working in New Zealand after the war this had appeal to those not so keen on the creosote ‘coconut-slice bachs’ of Vernon Brown and the Group.

The house in Dover Place designed for the Bairds by Franz in 1967 is, like the others predominately of concrete block, with Oregon beams and large north facing glass areas sitting above a tributary from Hobson Bay, deftly positioned to make the most of the sun and light available. Clerestory windows and a raised square light-well provide added illumination in the central kitchen and vestibule, strip windows strategically placed for privacy from the street also naturally lighting the south facing storeroom. The house is entered either along the side to a vestibule area, or from the ‘carporte’ (now garage) into the kitchen which looks across the large open lounge and out to the view and planting. Massive sliding floor to ceiling glass doors and fixed windows on north and west sides provide all day warmth to the family areas, while large decks project out over the terraced section below. Interestingly, Franz’s plans show a underfloor ducting system embedded in the concrete floor-slab for moving heated air around the house.

As with all of the houses plans, the foundations and engineering are detailed, the structure being part of the house rather than something it sits upon. A later house for Dr Phillip Lane and his wife Meg in Thames at the edge of a steep valley was particularly notable, and considered too difficult to build on but as the latest owners attest, it is still exactly as it was structurally and retains its sophisticated and practical elegance. Franz’s integration of structural design was transposed to large scale building shortly after his own house appeared in ‘Home & Building’. Airedale Street in central Auckland rose from Queen Street up to the ridge of Symond Street, and in 1961 the four story ‘Leview Building’ was constructed in the lower part, approximately were the extension of Mayoral Drive was built some years after. Built with a steel frame and large glass wall panels it was in many ways a test piece for a much larger building in Whangarei, designed and built for the Fletcher Trust and Investment company in 1963 on the corner of Rathbone and Roberts Streets.

At the home, while Franz was perusing his work from the office in Grafton then Gt South Rd, Patricia had built up a business (as well as caring for their two children) designing and making sporting wear – and producing gowns for Remuera debutante balls. Sprott Rd was briefly a workroom for several machinists before finding bigger but more expensive premise from which to operate. ‘Racquet Fashions’ expanded, importing material, making and selling clothes to shops all over New Zealand. Patricia also began exporting to Australia and spent much of her time traveling either in New Zealand or to suppliers and her outlets, always looking for new inspiration.

Between their two operations, in early 1964 Franz and Pat financed the building of a set of four units just off Great South Rd, not far from One Tree Hill. The units were flat roof, low maintenance one level concrete block and timber construction with small grass areas and carports. These were (later) sold off and helped finance a small beach-house north of Whangarei not far from Patricia’s original family home.

Throughout the 1960’s and into the 70’s Franz and Pat worked hard and built up their separate business’s, though time would also alter their relationship. Economic changes as Britain joined the EU and the ‘Holyoake years’ ending meant a rise in unemployment figures (from 200 to 4500.!) and a country teetering towards recession and instability. This was also the ‘public’ beginnings of the Green movement within New Zealand, and large scale protests against Nuclear Testing and the power station at Manapouri. Franz was later to become involved with the Green movement, having from early days actively sort ways to reduce material consumption in the construction of his projects.

Many of Franz’s buildings are still unknown, as his records, like so many architects, have either been tossed out, plans and drawings on paper eventually succumbing to the bin or perhaps recycling! Some designs from the era still exist such as the Clifton Apartments in Takapuna, a highly desirable sea-view address – again built by Fletchers. His use of concrete block and wood fitting well with his designs for buildings of all sorts. The Rolleston motel in Thames, a vet clinic in Mount Wellington for NZTG, commercial buildings in Auckland and Whangarei, houses of varying types across the city, all have endured and often provided their owners or inhabitants with thoughtful, elegant and practical shelter.

After he and Pat divorced in the mid 70’s Franz was employed as Senior Engineer and Architect by the Ministry of Works, in Lae, Papua New Guinea. Here he would meet his second wife Maria who was recording and archiving the songs of the indigenous highland tribes for the Lutheran Church. Returning to New Zealand some years later he and Maria lived outside Whangarei at Parau Heads where Franz becoming heavily involved with green issues and the local council’s lack of accountability around environmental practices.

Tragically, Franz died in 2010 after complications from an operation, barely years two after Pat passed away. Although no longer married, their combined energies and original determination to make a life in this city has in some ways nourished the culture and history of a whole country. As yet, Franz’s houses are still relatively unrecognized within both the architectural narrative and our wider built history. This is in part probably due to their distinctly utilitarian Bauhaus attributes and visual strength rather than their quality of planning and ideas. In fact these houses work incredibly well, many having only had cosmetic upgrades in bathroom and kitchen areas to make them completely delightful living experience over fifty years later – all of which is testament to Franz’s ability and considered approach.

Hopefully further investigation will identify many of his unknown works, and provide a valuable resource for those interested in this countries wider architectural and built history.

**********

Gregory J Smith.

Lost Property 2 – September 2011

Many thanks to all the owners and supporters. Any further information or corrections please use the contact page.